Supporting Language: Culturally Rich Dramatic Play

You are here

It’s circle time on a Monday morning in a South Texas Head Start classroom. The children have noticed that la paleteria (food stand selling frozen fruit popsicles and ice creams), the most recent dramatic play center theme, has been taken down and put away, and they are wondering what kind of center should replace it.

Mrs. Ramos invites them to talk about their weekend activities. Rodrigo says he and his grandmother went to the panaderia (bakery). Two children ask, “What is that?” Juanita explains, “That’s a bakery where you buy bread and cake.” Mrs. Ramos says she and her mother used to go to the panaderia when she was a child. The children smile.

The conversation turns to pan dulce (sweet bread). Some children say they buy it at the local grocery store or corner store. Others say their families buy it at their nearby panaderia. Mrs. Ramos says that could be the theme of the new dramatic play center. The children enthusiastically begin naming baked goods that their panaderia will sell, and Mrs. Ramos writes their suggestions down.

Culturally responsive centers

To identify culturally relevant themes, listen to children’s everyday talk. In Mrs. Ramos’s classroom, the children’s conversations about their family activities led them to create a panaderia in the dramatic play center. Culturally relevant dramatic play centers let young children draw from their experiences to enhance their play. Children reenact activities and observations from family life and share common events in their cultures. Authentic dramatic play leads to children’s meaningful learning—especially in language and vocabulary.

Here are some ideas for planning language-rich environments that help dual language learners (in this case, emergent Spanish/English bilinguals) develop communication skills. When you intentionally create interesting experiences for children, their play becomes deeper and more interactive.

Spark conversations through verbal mapping

To expose children to new vocabulary, practice verbal mapping—that is, describe to children what they are doing (or what you are doing) to introduce new words in a meaningful context. Remember to use new vocabulary words in conversations over and over again, because children need to hear and practice unfamiliar words many times to truly understand them. Teachers describe actions and objects that are important to children while in a familiar and meaningful setting. The setting for the classroom might be a bodega, a paleteria, or a panaderia.

Jorge explains that in his neighborhood bakery, you use pinzas para pan, or tongs, to pick up bread. Mrs. Ramos sees this as an opportunity to reinforce the word tongs. She hands two wooden blocks to Jorge and says, “Good morning, sir. I’m delivering the two tongs the manager ordered for the bakery.” Although tongs is a new word for the children, they immediately integrate it into their speech and play. The cashier tells the next customer, “Please give me your tray so I can ring up your bread. Leave the tongs over there.” Teachers also engage in verbal mapping when they talk about the types of bread customers buy. Without disrupting play, Mrs. Ramos asks questions, supplies vocabulary, and extends the conversation to support children’s language development.

Provide new props to extend children’s play

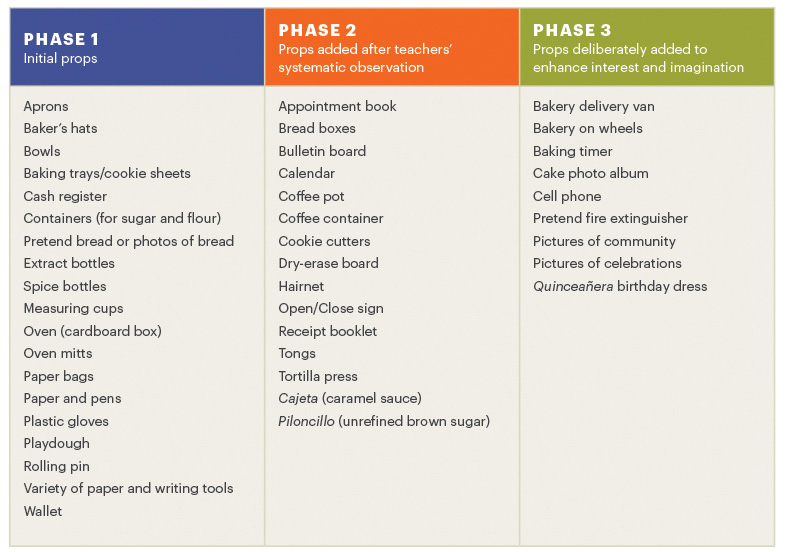

Props can be added in phases to build on children’s knowledge and hold their interest. Here’s how Mrs. Ramos set up the panaderia.

Phase 1

Provide basic bakery props. Offer—or invite families to contribute—common objects and tools, such as photos/pictures of familiar breads, aprons, spice and extract bottles, plastic mixing bowls, wooden spoons, rolling pins, and other kitchen products or tools.

Phase 2

Add more props based on careful observation of children’s interactions. After Mrs. Ramos observed children talking about delivering cakes for weddings and quinceañeras (girls’ 15th birthday celebrations), she introduced a calendar. The children marked the dates when cakes had to be delivered to or picked up by customers. Other items provided included cookie cutters and a receipt booklet.

Phase 3

Add props that enhance the theme. Mrs. Ramos placed a pretend fire extinguisher in the bakery. This extended children’s imaginations (and vocabulary) as they role-played burning bread and putting out a fire in the oven. She also supplied objects like a bakery timer, cake photo album, and pictures of celebrations.

Try placing new props in the center for children to discover first, then explain how to use them. Or teachers might introduce the new props through role-playing, as Mrs. Ramos did with the tongs.

This dramatic play center reflected the Spanish-speaking children in the class. But classes have all sorts of cultural mixes. Regularly assess the materials and props in the dramatic play center to make sure they accurately reflect all of the children and families in your class and accommodate the children with disabilities. Add props that encourage children to talk to each other and to their teacher. When the excitement over a certain dramatic play center fades, offer new props or change the theme.

Make it a print-rich setting

Create a welcoming print-rich dramatic play center. Add functional labels, pictures, books, and other materials reflective of children’s cultures, such as familiar recipes, photos of cultural sweet breads, and spice or extract bottles (for example, vanilla, cinnamon, or piloncillo—unrefined brown sugar). Mrs. Ramos labeled the panaderia shelves with the names of different breads and other baked goods that children had heard their families talk about, such as empanadas, conchas, and orejas. Now, they could see how those words were spelled. This encouraged them to write the words as they were ordering or selling sweet bread or creating new bread recipes.

An interesting space encourages children to stay engaged. Children notice the print and learn that it symbolizes language. Using the props, they learn the everyday functions of writing and literacy. When Mrs. Ramos placed an Open/Abierto sign on the panaderia counter, some children said, “Ya esta abierta la panaderia!” (“The bakery is open!”).

Place useful labels so that children can touch them—even copy and trace them—and help organize the materials. Mrs. Ramos made labels in Spanish and English for the names and prices of specific baked goods. The “Open/Abierto” sign and the different labels helped children organize their thought process as they created sequenced role-playing episodes. The labels also worked as resources to scaffold the children’s language and help with reading.

Conclusion

Children’s language development is enhanced by intentional support from teachers, interaction with peers, and opportunities to practice their new communication skills. We hope our examples inspire you to create dramatic play centers that reflect your children’s communities, cultures, and experiences outside of school. Center themes encourage children to play together and talk about what is personally meaningful to them. They can have fun using new words in a safe, comfortable setting.

Prop Suggestions for the Panaderia

Irasema Salinas-González, EdD, is an associate professor and coordinator of the early care and early childhood studies program at the University of Texas–Rio Grande Valley (UTRGV). During her 29 years in the bilingual and early childhood education fields, she has been a preschool and kindergarten teacher and reading specialist, and has worked with preservice and in-service teachers. She received her MEd in Early Childhood Education from the University of Texas–Pan American and her EdD in Bilingual Education from Texas A&M University–Kingsville. Her work focuses on language and literacy development of young dual language learners through play, the development of cognitive skills of dual language learners through play-based learning, and creating engaging classroom environments for young dual language learners.

María G. Arreguín, EdD, is an associate professor of early childhood and elementary education in the department of interdisciplinary learning and teaching at the University of Texas–San Antonio. She earned her doctoral degree in Bilingual Education at the Texas A&M University–Kingsville. Her research on dual language education, early childhood education, dyad learning and dialogue, and critical science pedagogy illuminates the intricacies of cultural and linguistic factors that influence minority children’s access to education in early childhood and elementary bilingual settings.

Iliana Alanís, PhD, a native of South Texas, is a professor of early childhood and elementary education in the Department of Interdisciplinary Learning and Teaching at the University of Texas at San Antonio. She taught children in bilingual first- and second-grade classrooms while earning a master’s degree in curriculum and instruction with a concentration in bilingual education from the University of Texas–Pan American.