Focus on Ethics. Professional Boundaries in Early Childhood Education

You are here

Professional boundaries was posed to us as a possible topic for the Focus on Ethics column. Because we knew that it was an important consideration in all helping professions and that it had not been considered in depth in early childhood education, we were interested in exploring the topic. As we learned more, we came to realize that professional boundaries had as much to do with the professionalism of our field as it did with ethics.

Boundaries are an integral part of the identity of every helping profession. Being aware of and honoring boundaries between practitioners and those they serve is an important professional responsibility. The purpose of this column is to examine this issue with the hope of beginning a conversation about professional boundaries in early childhood education. To help start this discussion, our column is informed by literature from other fields as well as input from experts in early childhood.

Because the topic is large and complex, we have chosen to focus this column on discussion of boundaries that involve early childhood educators and the families and children they serve. There are also boundary issues between educators and their colleagues and program administrators. We look forward to exploring those in a future column.

Situations involving boundaries

The following scenarios raise some questions about professional boundaries in early childhood settings.

A family invites you to a party. Is it okay to go?

You supplement your income by selling cosmetics at home parties. Is it okay to ask a child’s family to host a party?

A family offers you an all-expense paid vacation for your honeymoon. Should you accept?

A child in your class lives near you, and the family car is broken. They ask you to drive the child to and from school until they can afford to get their car fixed. Should you agree?

You are hosting a fundraiser for a political candidate. Is it okay to invite families of children in your class?

A family member tells you that she is having trouble sleeping. Is it okay to tell her about a drug that helps you sleep?

The father of a child in your class asks you to go out to dinner to discuss his child’s progress. Is it okay to go out with him?

What are professional boundaries?

During any year, teachers may be faced with a myriad of situations and questions, such as the ones just listed, that involve their personal and professional relationships with young children and families. In the helping professions (medicine, social work, nursing, etc.), there are lines that professions draw between professional and personal relationships that are referred to as professional boundaries. Professional boundaries help differentiate between actions that are professionally appropriate and those that are inappropriate or unprofessional. They can be represented through the metaphors of lines, fences, or guardrails (Doel et al. 2010; Austin et al. 2006).

Professional boundaries are broader and less clear-cut than ethical principles. Ethical principles describe what professionals must do or must not do. They are consistent across programs (e.g., we must respect confidentiality. We must not endanger children). Professional boundaries are more situation specific and vary more based on circumstances, community, the kind of program, and culture. Early childhood education as a field is in the process of asserting its right to be called a profession and defining what this means. As members of a profession, early childhood educators, like others in helping professions, need to be thoughtful about recognizing and managing professional boundaries. They are especially important to explore because there are currently no set rules or established norms for professional boundaries in early childhood settings. Guidelines set by other helping professions can help to identify boundaries for early childhood educators.

Why are professional boundaries important?

While their relationships with families will vary depending on the type of program in which teachers work—those in family child care may be quite different from those in a public school kindergarten—in every case, the relationship between teachers and families is not one of equals. Early childhood teachers have power: They have professional knowledge, access to sensitive information, and are authorized by the community to care for and educate young children. They have the potential to significantly impact the life of a child during the most important years of development, and they have the power to support or hinder each family’s ability to nurture their child.

Families have less power in this relationship than the educator. Most know less about young children’s development and learning than teachers do. They are required to share personal information with staff who may come from a different ethnic, linguistic, cultural, or socioeconomic background. All families entrust their children to teachers throughout their education, but in the early years, when children are most vulnerable, these relationships can have a particularly strong impact.

Professional boundaries help to ensure that teachers use their power well and fairly. Professional teachers understand that their purpose is to use their knowledge and skills to build relationships that support the development of children and that work in partnership with families in the task of child rearing. Families trust early childhood educators to act in the best interests of the child and family. To maintain that trust, they must practice in a manner consistent with professional standards, including the NAEYC Code of Ethical Conduct. They must abstain from seeking personal gain at a family’s expense and refrain from actions that might jeopardize the child–family relationship. Regardless of the context or length of interaction, the professional–family relationship should respect and protect the family’s dignity, autonomy, and privacy.

Professional, social, and personal relationships in early childhood education

Aran enters the infant room with 8-month-old Shanti. Lara, the teacher, beams and sings, “I’ve been waiting for you to come to this place. Waiting for you to come to this place. Wherever you’re from, I’m so glad you’ve come. I’ve been waiting for you to come to this place!” Shanti squirms with apparent delight. With a smile Aran bids her daughter goodbye and places her in Lara’s arms, giving Shanti a kiss and Lara a hug.

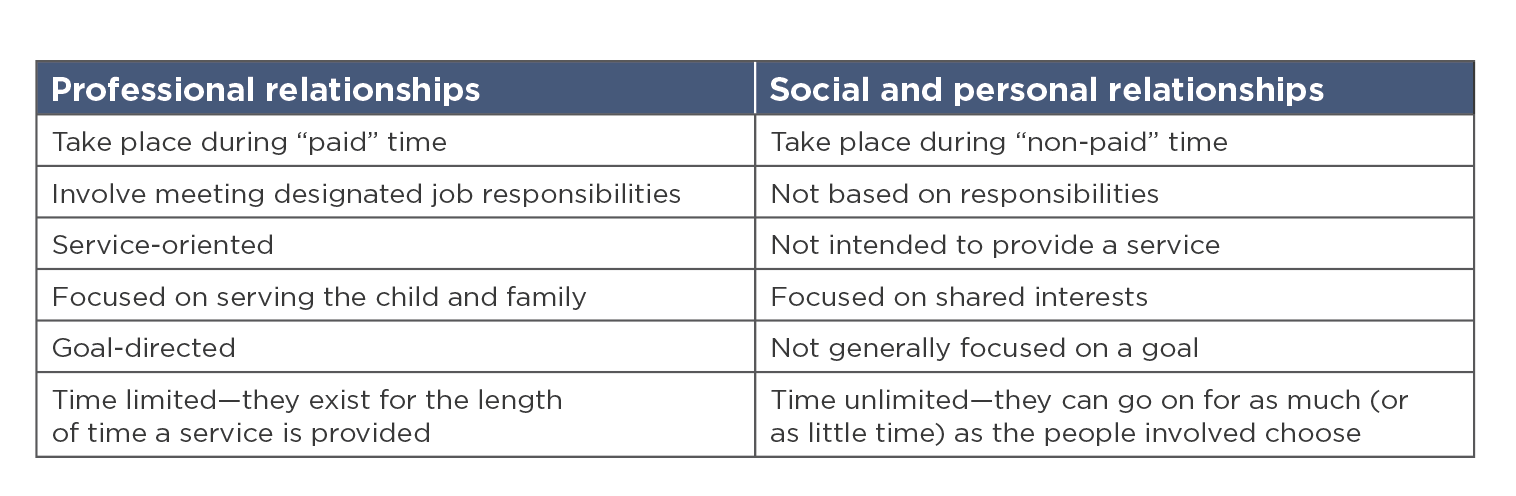

The boundaries between the family–professional partnership and friendship can easily become blurred in early childhood settings. Early childhood educators work closely with families, and early education settings are often more relaxed and informal than other professional settings. See the table below for some of the differences between social and personal relationships and professional relationships.

Professional relationships can appear quite differently in early childhood settings than they do in other helping professions. Unlike nurses, doctors, librarians, counselors, social workers, or even teachers in most elementary school settings, early childhood educators have a particularly intimate relationship with families:

- They are with children longer and more often—sometimes as many as 40 hours a week.

- They have close, affectionate, and physical interactions with children, including caring for children’s most intimate physical needs.

- They engage with children and families for a lengthy proportion of a child’s life, longer than any but the closest family and friends.

- They have sensitive information about the emotional and social—and sometimes financial—life of the family, including details about relationships between family members and their child.

It takes extraordinary trust to allow a stranger to have that kind of closeness with one’s child and family. Early childhood educators build that trust by ceasing to be strangers, by being human and vulnerable, and by accepting a degree of intimacy. They sustain that trust by developing good relationships and by honoring professional boundaries.

Additionally, it is not uncommon, especially in smaller communities, for teachers to have more than one kind of relationship with a family. For example, a teacher and a family member may sing in the same choir, their children may be on the same soccer team, or they may be relatives or have grown up together. When teachers have a dual relationship (a personal connection outside of the professional role) with a family member, awareness of professional boundaries becomes especially important.

Professional boundary crossings and violations

Most early childhood educators have had experiences in which they are aware that a boundary has been, or is likely to be, crossed. Boundary crossings are brief excursions across professional lines of behavior that may be inadvertent, thoughtless, or even a purposeful attempt to meet the needs of a child or family. They are non-exploitative. Boundary violations, on the other hand, are exploitative or potentially harmful to children and families. They may not be recognized or felt until harmful consequences occur (Doel et al. 2010).

We asked a group of early childhood educators whose work we respect, who have extensive experience in the field, and who have an interest in ethics and professionalism to help us think about professional boundaries. They recounted many experiences with boundary crossings and boundary violations, and some themes (recurring, significant ideas) and examples emerged.

For boundary crossings, the examples fell into the following themes:

- socializing (e.g., attending a party hosted by a family)

- rescuing (e.g., driving a child home when the mother needs to take an emergency trip)

- seeking favors (e.g., asking a parent for professional advice)

- proselytizing (e.g., advocating for religious or political beliefs)

- disclosing information (e.g., extensive sharing of a personal problem with a parent)

- giving advice beyond the scope of one’s role or expertise (e.g., offering marital advice unrelated to the child)

- breaching confidentiality (e.g., sharing pictures of an enrolled child on personal social media)

For boundary violations, examples were related to these themes:

- showing favoritism or bias (e.g., consistently greeting one group of children and families with more warmth and enthusiasm than others)

- accepting large gifts or favors (e.g., accepting an all-expenses paid trip from the family of a child you teach)

- engaging in an intimate relationship (e.g., dating the father of an enrolled child)

- seeking personal gain (e.g., asking a family member to purchase something sold by the teacher)

Creating and sustaining professional boundaries

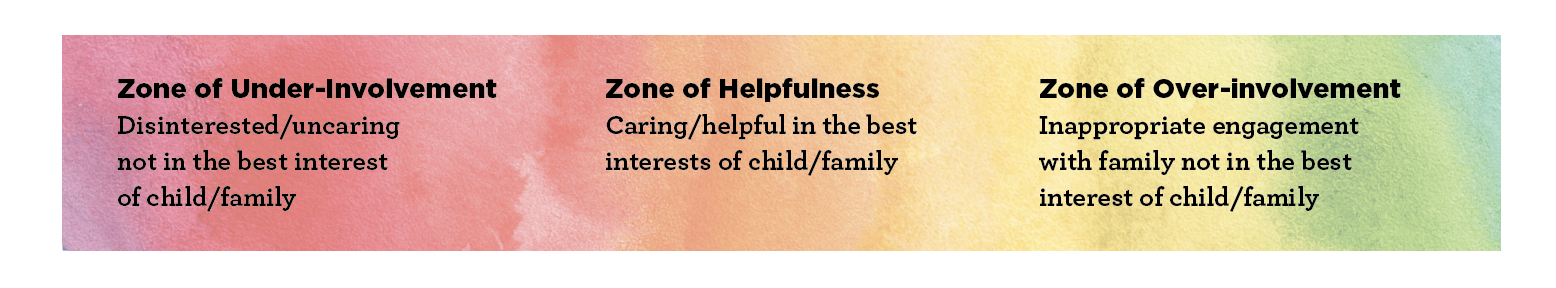

Because identifying and maintaining boundaries is the responsibility of the teacher, not the family, it is helpful to have a structure for thinking about them. Teachers and administrators can use a continuum, called the “The Zone of Helpfulness” (Kemp 2014), which has been developed and used by the field of nursing and adapted here for early childhood education (see the illustration of this continuum below). In the middle of the continuum are boundaries that support caring, helpful, and productive teacher–family relationships. Setting and keeping appropriate professional boundaries varies depending on the setting, community, culture, family, and the age of the child involved. For example, in small or close-knit communities and among some cultural groups, families often invite teachers to events like weddings, birthdays, and graduations. Teachers who regularly fail to attend such events may be viewed as uncaring, and the teacher–family relationship could be damaged. In other settings, attending these kinds of events this would be regarded as inappropriate.

There is a gradual transition between the middle and the ends of the continuum, which illustrates the fact that professional boundaries are less clear cut than ethical principles. At the same time, there are limits: at either end, actions can lead to detrimental consequences to the family, the child, or the teacher–family relationship. For example, on the “under-involved” end of the continuum, in some settings failing to develop a good relationship with members of a family can be a problem. However, on the “over-involvement” side, crossing the boundary from friendly to friendship may compromise the teacher’s ability to remain objective and can damage relationships with the other families in the program. Additionally, it may add responsibilities to the teacher’s role and lead to burn out or disappointment when they are no longer able to maintain these close relationships.

How do you know when you are about to cross a boundary?

Initially, when we asked our selected group of early childhood practitioners about how they knew when they were approaching a boundary crossing or violation and how they addressed these in their work, many of them responded that they were not sure and had never thought about it. They acknowledged that the issue of professional boundaries had not been a part of their preparation to be a teacher or administrator. Upon further reflection, several recalled an uncomfortable time when they or a colleague had been faced with a challenging situation involving a professional boundary. Most indicated that they used past experience and intuition to guide their decision-making and actions. Several indicated that they wished there had been some professional guidance available.

Based on our study of other human service fields’ guidelines and the feedback we received from our consultants, we identified questions that early childhood educators can ask themselves to determine whether a situation involves a professional boundary. (See “Does a Situation Involve Boundaries?” below for these reflection questions.)

Customs and expectations vary enormously between and within families and cultural groups; because of this, most boundary issues are situational. What may seem clear in one situation might not be clear in another program, culture, community, or even with families who share the same culture, as is highlighted in the following vignette.

When members of Kainoa’s extended family bring Kainoa to school, they greet teachers with hugs and a kiss. They refer to teachers as “aunty.” They often bring them bananas, avocados, or papaya from their garden. Kainoa’s grandparents speak to teachers in “pidgin”—a nonstandard English dialect.

Makena’s family, who share Kainoa’s culture, are friendly but reserved. They speak about their Hawaiian culture proudly. They always use standard English when talking to teachers but use dialect when speaking to their child or one another.

How should teachers respond to these two families? Should they refrain from returning Kainoa’s family’s hugs because it would breach a professional boundary? Should they offer hugs and speak in dialect to Makena’s family because they share the same culture as Kainoa’s family? We live in diverse communities with diverse expectations of early childhood teachers and families. Even in the same community, as in the above example from Hawaii, boundaries vary and few are absolute. Being attentive to individual families and their needs helps teachers to choose professional behavior that acknowledges and accepts differences and demonstrates respect for all children and families.

Does a Situation Involve Boundaries?

Here are some reflection questions that may help you determine whether you are about to cross a boundary as a professional.

- Why is this situation bothering me?

- Does the action I am considering primarily support the needs or well-being of the child and family, or does this action primarily support my needs or well-being?

-

Does this action involve fairness and equity?

- Does it provide equal benefit to all of the children and families?

- Might this action create an “in” group and an “out” group?

- Might it be seen as favoring those of a particular race, culture, or socioeconomic group?

- Will this action cause a family to become dependent on me? Will they be able to manage if I am not available to them?

- Am I sharing highly personal information that is unrelated to work with children and families?

- Am I giving advice on an issue that I do not have training to address?

Guidelines for early childhood educators

As of this writing, there is no set of established rules or conventions to guide early childhood educators as they navigate professional boundaries. The professional associations of many human service fields have guidelines to help their members establish and maintain appropriate boundaries. We have reviewed guidelines from nursing, psychology, early intervention, social work, and elementary, secondary, and special education.

These guidelines are designed to inspire confidence by directing professionals to treat all clients with respect; to establish clear, appropriate and culturally sensitive boundaries; to carefully manage dual relationships; and to refrain from inappropriate physical and financial relationships (The NASW Code of Ethics; Early Intervention Specialists’ Code of Ethics; American Nurses Association’s Code of Ethics; and “A Nurse’s Guide to Professional Boundaries,” published by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing, all served as helpful resources).

Until our field has created agreed-upon guidelines, we suggest some first steps based on work in other fields (Barron & Paradis 2010; Kemp 2014; National Council of State Boards of Nursing 2018), on your professional judgment, and on responses from contributors to this column:

- Reflect on your professional role and its limits.

- Consider what a family can or should expect from you while their child is in your care.

- Plan how you will establish and communicate boundaries to families.

- Reset boundaries if they have been blurred, such as when you have a friendship with a family before a professional relationship begins.

- Think about the differences between being friendly and being a friend. Taking into account your program, community, and the cultural groups you serve, consider where you will draw a line between personal and professional relationships.

- Resolve not to show favoritism to any child (or group of children) or to any family (or group of families).

- Determine the personal information that you can or want to share with families that will support your professional relationships with them, and manage social media accounts accordingly. Remember that professional relationships are finite—they have a beginning and an end. You will have future opportunities to have a personal relationship with a family when the professional relationship is over.

P-2.11—We shall not engage in or support exploitation of families. We shall not use our relationship with a family for private advantage or personal gain or enter into relationships with family members that might impair our effectiveness working with their children.

Where do we go from here?

Section P-2.11 in the NAEYC Code of Ethical Conduct addresses professional boundaries in terms of what early childhood educators should not do. Although this is helpful guidance, it does not explain the importance of or the reasoning behind these ethical principles. Additionally, it does not describe or provide guidance about navigating the professional boundary issues that early childhood educators face.

In this article we have laid a foundation for exploring a topic that has not received very much attention in early childhood education: we outlined what professional boundaries are, how boundaries in the early childhood field are similar and different to those in other professions, how boundary transgressions can occur, and offered general guidelines that can help early childhood educators make decisions regarding professional boundaries related to working with families.

We have always engaged NAEYC members in dialogue to help us develop guidelines for dealing with ethical issues. Similarly, we would like to know your thoughts about professional boundaries.

- Do you think professional boundaries should be an important consideration for the field of early childhood education?

- Have you encountered boundary issues similar to those mentioned here?

- What other professional boundary issues have you encountered that are not mentioned here?

- What would be helpful to you in addressing boundary issues in your workplace?

We look forward to hearing your responses to these questions. Please email them and any thoughts, experiences, and suggestions relating to professional boundaries to [email protected] You may also join in the conversation in an upcoming HELLO thread called “Professional Boundaries in Early Childhood Education.”

Special thanks

Our work on professional ethics has always been informed by discussions with groups of early childhood educators who share their best thinking about a particular ethical issue. Since this type of meeting is not possible at this time, we contacted some knowledgeable colleagues—teachers, administrators, and adult educators—most of whom have collaborated with us in our work on ethics. We thank the following people for sharing their insights about professional boundaries: Ingrid Anderson, Spring Busche-Ong, Marjorie Fields, Ginger Fink, Julie Lee, Nina Martin, Carol Morgaine, Meir Muller, Sherry Nolte, Julie Powers, and Anita Trubitt. We also wish to thank Early Learning Indiana for bringing this important topic to our attention.

References

American Nurses Association. 2015. Code of Ethics for Nurses with Interpretive Statements. https://www.nursingworld.org/coe-view-only.

Austin, W., Bergum, V., Nuttgens, S., & Peternelj-Taylor, C. (2006). "A Re-visioning of Boundaries in Professional Helping Relationships: Exploring Other Metaphors." Ethics & Behavior 16 (2): 77–94.

Barron, C., & N. Paradis. 2010. “Infant Mental Health Home Visitation.” ZERO TO THREE 30 (6): 38–43.

Bryson, S. (n.d.). “Understanding Professional Boundaries for Workers and Supervisors.” Presentation. London: Directory of Social Change. https://www.dsc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Understanding-Professional-Boundaries.pdf.

Doel, M., Allmark, P., Conway, P., Cowburn, M., Flynn, M., Nelson, P., & Tod, A. 2010. Professional Boundaries: Crossing a Line or Entering the Shadows? British Journal of Social Work 40 (6): 1866–889.

Early Intervention Specialists. N.d. “Code of Ethics for Early Intervention Specialists.” https://admin.abcsignup.com/files/%7B07D0901F-86B6-4CD0-B7A2-908BF5F49EB0%7D_59/Code_of_ethics.pdf.

Kemp, J. 2014. Moving On: Professional Boundaries and Transitions in Early Intervention, Education, and Care. https://coursemedia.erikson.edu/eriksononline/WebEx/Webinars/Fall14/Moving_On_Professional_Boundaries_and_Transitions.pdf.

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. 2018. “A Nurse’s Guide to Professional Boundaries.” Brochure. www.ncsbn.org/ProfessionalBoundaries_Complete.pdf.

NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children). 2011. “Code of Ethical Conduct and Statement of Commitment.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. NAEYC.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/Ethics%20Position%20Statement2011_09202013update.pdf.

NASW (National Association of Social Workers). 2017. “Code of Ethics of the National Association of Social Workers.” https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English.

Stephanie Feeney, PhD, is professor emerita of education at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. She is coauthor of NAEYC’s “Code of Ethical Conduct” and NAEYC’s books about professional ethics. She participated in the development of supplements to the code for adult educators and program administrators and has written extensively about ethics in early care and education. She is the author of numerous articles and books, including Professionalism in Early Childhood Education: Doing Our best for Young Children and coauthor of Who Am I in the Lives of Children? [email protected]

Nancy K. Freeman, PhD, is professor emerita of education at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, where she was a member of the early childhood faculty. She has served as president of NAECTE and was a member of its board for many years. Nancy has written extensively on professional ethics since the 1990s, and has been involved in the Code’s revisions and in the development of its Supplements for Program Administrators and Adult Educators. [email protected]

Eva Moravcik is professor of early childhood education at Honolulu Community College and the site coordinator of the Leeward Community College Children’s Center in Pearl City, Hawaii. She is coauthor of Who Am I in the Lives of Children? (with Stephanie Feeney and Sherry Nolte) and Meaningful Curriculum for Young Children (with Sherry Nolte). [email protected]