The Play’s the Story: Creating Play Story Booklets to Encourage Literacy Behaviors in a Preschool Classroom

You are here

Navigating the Paradoxes Between Early Childhood Education and Play: An Introduction to Ron Grady’s Article | Ben Mardell, Voices executive editor

“Play promotes joyful learning that fosters self-regulation, language, cognitive, and social competencies as well as content knowledge across disciplines. Play is essential for all children.”

One of the nine principles of child development and learning that informs practice, this declaration, part of the latest edition of NAEYC’s position statement on developmentally appropriate practice, reaffirms our field’s commitment to children’s right to play. At the same time, the position statement acknowledges that it can be a struggle to incorporate play into formal learning situations, a reality that disproportionately impacts children of color (Souto-Manning 2017). David Kuschner (2012) notes tensions or paradoxes between the nature of play and the nature of school—for example, in play, children are in charge; at school, adults have learning goals for children. This can lead to a focus on academic goals at the expense of time to play.

Into this context comes Ron Grady’s compelling article “The Play’s the Story: Creating Play Story Booklets to Encourage Literacy Behaviors in a Preschool Classroom.” Grady recounts how, tasked with bringing play into a preschool program focused on discrete academic domains, he was often told by his new colleagues, “We like play, and we know the children need it, but there just isn’t enough time in the day.”

Grady takes on a central paradox between play and school—between children’s agency and adult learning goals—by aiming to change the situation from one of “either/or” to “yes/and.” His creative solution is storybooks that he, with input from the children, creates based on their play. With photographs of the children at play and text describing their play with occasional quotations, Grady makes a series of books to display in the classroom library. These books are of great interest to the children, and so they are motivated to read. This fosters the literacy behaviors Grady and his colleagues wish to encourage. By documenting the children’s play and making it visible, he has made reading books culturally relevant and personally meaningful.

Grady is creating the conditions for his children to engage in playful learning (Pedagogy of Play 2016). His children are able to choose what to play, whether to read a book, and which book to read. They are able to wonder, exploring the world of imagination that play opens up. Referring to “my friends’ books” when asking for a storybook to be read, they experience the feelings of pride and joy that playful learning can elicit. Grady’s children are doing what they want to be doing (playing and reading books about their play), which is exactly what he wants them to be doing.

It is noteworthy that the children in this case are 2- and 3-year-olds. Noteworthy because, of course, they want to play, and they also want to learn about reading and books. For the children, their play and their learning occur together. When given a steady diet of books that are meaningful to them, these young children develop age-appropriate book handling skills, knowledge of print, and knowledge of their world.

Grady’s article is the fruit of his teacher research. Reading his piece, one cannot but think this endeavor involved playful learning for him too. As he explains, making the storybooks was fun. And like play, this was more than simply entertainment. The work was challenging, Grady notes. It was an intellectual adventure, involving an exploration of literature on literacy development and on play. And it was joyful, supporting the learning of young children.

Near the end of his article Grady shares an anecdote involving him reading a storybook to his student Jenna about her washing baby dolls. Finishing the book, Jenna exclaims, “Let’s do it again.” This is exactly how we want young children to respond to books—to find reading meaningful and motivating. On finishing the article, I have the same reaction as Jenna’s—let’s do it again. One hopes that Grady will be doing this again, continuing to further our understanding of developmentally appropriate literacy instruction for young children and of ways to navigate the paradoxes between early childhood education and play.

References

Kuschner, D. 2012. “Play Is Natural to Childhood but School Is Not: The Problem of Integrating Play into the Curriculum.” International Journal of Play 1 (3): 242–249.

Pedagogy of Play Research Team. 2016. “Towards a Pedagogy of Play.” Working Paper. http://pz.harvard.edu/sites/ default/files/Towards%20a%20Pedagogy%20of%20Play.pdf.

Souto-Manning, M. 2017. “Is Play a Privilege or a Right? And What’s Our Responsibility? On the Role of Play for Equity in Early Childhood Education.” Early Child Development and Care 187 (5-6): 785-787.

About the Author

Ben Mardell is a principal investigator at Project Zero at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. He has worked as a preschool and kindergarten teacher and currently works on the Pedagogy of Play and Children are Citizens projects.

[email protected]

The Play’s the Story: Creating Play Story Booklets to Encourage Literacy Behaviors in a Preschool Classroom

The idea for this research was born out of a seemingly irresolvable dilemma: reconciling having the time and space for play and the time and space for reaching early learning standards and outcomes. A couple of years ago, I accepted a position as a collaborating teacher tasked with integrating play into a preschool curriculum—one that was historically oriented almost wholly toward academic domains and with very little time for play. “We never have time for play,” teachers would often say. “We like play, and we know the children need it, but there just isn’t enough time in the day.” Tacitly beginning these phrases was the clause “Because of all of the requirements of the academic pieces of our curriculum . . .”

These teachers were not alone in their attitudes toward play. For many years, a disconnect has existed: Researchers and advocates for play have raised serious concerns with how little room there is for play in educational settings (Hirsh-Pasek et al. 2009). In the field, educators—like the ones in my new preschool—have tended to view play and academics as mutually exclusive; that “play is nice, but not necessary” (Roskos et al. 2010).

While I understood this concern, my professional learning and experiences led me to a different viewpoint: play can positively influence learning and growth across developmental domains. I agreed with Kuschner (2012), who wrote, “true play, [like that of] the solitary child in the dress-up corner, the rough-and-tumble play of the children on the playground, the mini-dramas created by friends in the block center”—as opposed to adult-defined, goal-oriented activities—should comprise a central piece of early childhood education (248). Yet is it possible to have the time and space for play and the time and space for achieving expected standards and learning outcomes in early childhood?

I resolved to find out. I decided to investigate how play could support and scaffold a favorite domain of so many early childhood professionals—language and literacy. Rather than using the go-to texts in classrooms like nursery rhymes, fairytales, and other texts (especially fiction) by children’s authors, I wanted to find out whether play could become the story. I aimed to answer these questions:

- Will stories created from children’s play (play stories) promote early literacy behaviors in 2- and 3-year-olds?

- If so, which literacy behaviors will play stories promote?

- Will play stories influence children’s ongoing and future classroom play?

- How will children connect with the play stories that feature them as central characters?

Answering these questions would help me and my colleagues incorporate play in our classrooms and have a strong rationale that we could share with others.

Review of the Literature

Spurred by the contradictory perspectives on play and literacy, I dove into the research. Specifically, I looked at early literacy development and engagement, the links between play and emergent literacy, and the connections among story, play, and children’s personal experiences. My research was grounded in practices inspired by the Reggio Emilia approach, which recognizes and respects children’s agency as well as teacher documentation of children’s learning (Hendrick 1997; Wurm 2005; Stacey 2015)—the kind of documentation that could guide me in answering my questions.

The studies I read revealed key findings that framed my investigation. Seminal studies of early literacy have shown

- Children’s earliest experiences and knowledge build a foundation for later literacy success. Early childhood educators can affect what and how children learn to read and write through intentional instruction and playful experiences, including reading aloud storybooks and other texts (Dickenson & Sprague 2001).

- Children display emergent literacy skills and behaviors during the early childhood years as they develop into conventional readers and writers. These include concepts of print (Clay 1975) and narrative skills.

- While emerging in literacy, children as old as 5 and 6 will focus primarily on pictures as they build connections between oral language (including oral storytelling) and what appears in print in a book (Sulzby 1985).

- Children bring their own knowledge and experiences to literacy activities, and literacy learning is not a solitary event. Children grow in literacy through social interactions and within social and cultural contexts, including during play (Saracho & Spodek 2006).

- Young children’s storytelling reveals emerging narrative knowledge and, important for the purposes of this study, invites us to consider a child’s perspective on many, many things, including (but not limited to) their own lives (Paley 2004; McNamee 2015).

In addition to these studies, I found a rich trove of literature related to play, including the connection between play and early literacy. Play is a central “leading” activity of preschool (in the Vygotskian tradition), meaning that play—especially pretend play—scaffolds and propels children’s thinking and cognitive growth (Diamond et al. 2007). It deals, at least implicitly, with themes or concerns central to children’s lives, including peer relationships and the development of empathy (Corsaro 2012; Bodrova & Leong 2015; Mardell et al. 2016). Also, studies have demonstrated the potential of play to foster early literacy, especially encouraging literacy behaviors and developing narrative skills (Roskos & Christie 2011). “Successful early readers,” Margaret Meeks writes, “discover that the [written] story happens like play. They enjoy the story and feel quite safe, even with giants and witches, because they know that a story, like the house play under the table, is a game with rules” (1982, 37).

The final significant body of work that I reviewed focused on young children’s personal experiences, which can be difficult for adults to access. A young child cannot offer direct insights and may not be able to articulate certain states, feelings, meanings, and intentions. Knowing this, early educators and researchers have used three methods—photography, play, and story—as meaningful ways to gather information about children’s personal or internal experiences. Photographic methods tend to involve taking photos and videos of children, then re-presenting them at communal gathering times to reflect upon with children (Einarsdottir 2005; Serriere 2010). Play can reflect and showcase children’s inner thinking, emotions, and personal experiences. Storytelling reveals emerging narrative knowledge and invites us as educators to consider a child’s perspective on their inner and outer lives.

Based on what I read, I knew that these findings represented the highest level of what I might expect for the 2 1/2- to 3-year-old children in my classroom. Each of these studies was encouraging, and I was anxious to create the materials, collect the data, and analyze this information to answer my questions.

Methodology

Researchers have observed literacy behaviors in very young children looking at storybooks (Lee 2011). However, no one has examined how pictures of children’s play might spark literacy when those photographs are compiled into a book. Similarly, photographic documentation of children’s activities within a classroom are known to spur discussion and insight into experience (Einarsdottir 2005; Serriere 2010; Clark 2017). However, these pictures are not compiled in a way that mirrors the sorts of texts which will dominate children’s experiences as they move through the early years of schooling and care. My investigation attempted to fill those gaps in the research.

Researchers have observed literacy behaviors in very young children looking at storybooks (Lee 2011). However, no one has examined how pictures of children’s play might spark literacy when those photographs are compiled into a book. Similarly, photographic documentation of children’s activities within a classroom are known to spur discussion and insight into experience (Einarsdottir 2005; Serriere 2010; Clark 2017). However, these pictures are not compiled in a way that mirrors the sorts of texts which will dominate children’s experiences as they move through the early years of schooling and care. My investigation attempted to fill those gaps in the research.

To carry out my investigation, I turned to my class: a group of nine girls and six boys. All came from two-parent families; all but one were White. Our class was one of 12 classrooms in a division that is part of a larger preschool through grade 12 private school. In addition to me, there was one other teacher in the classroom who had been teaching for two years. Our school, and particularly our classroom, allocated two broad periods each day for child-directed, open-ended play. These sessions were scheduled at morning arrival time (from around 7:30 a.m. to 9:00 a.m.) and from 10:00 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. Occasionally, we had specials (art, music, or movement) that interrupted the children’s play; however, these were at most a few times a week.

Our classroom was divided into several open-ended areas: a reading rug, a meeting rug, a sensory area, an atelier, a large table for dining, and areas for dramatic and constructive play. We also had a little nook for our two guinea pigs, Chester and Silas. These were the areas where I observed and began to record my children’s play and create the play story booklets.

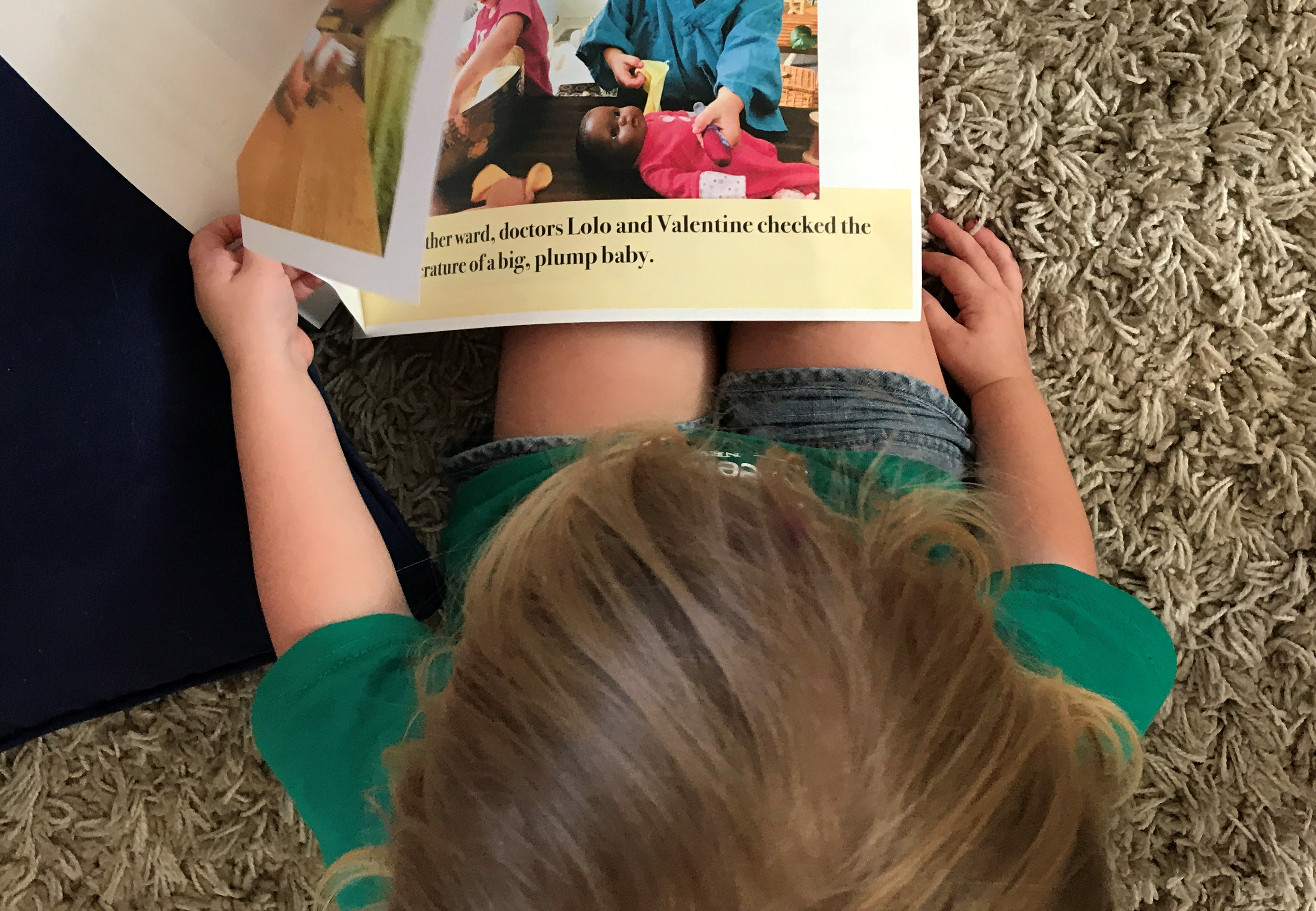

Creating these 4- to 5-page booklets was the easy part—not to mention fun! I used my phone camera to take pictures of the children during our periods of open-ended, child-directed play. Given that this was already an established norm in our classroom life, it did not require any extra time on my part. Next, I chose the photos for the play stories, focusing specifically on photographs that showed the children engaged in some form of dramatic play. These included children who adopted the role of a character for themselves or children who transformed a figure, such as a bear or a tiger, into a character.

Play can positively influence learning and growth.

After choosing the pictures, I placed them into a Keynote file and began creating the booklets. These, I formatted simply. The first page contained a large photo of the children’s play and a title. Subsequent pages contained either photos alone, which the children could interpret and reinterpret while telling their stories, or photos and text. This text was a blend of words and phrases used by the children during their play and my own narration, based on the direction the play took.

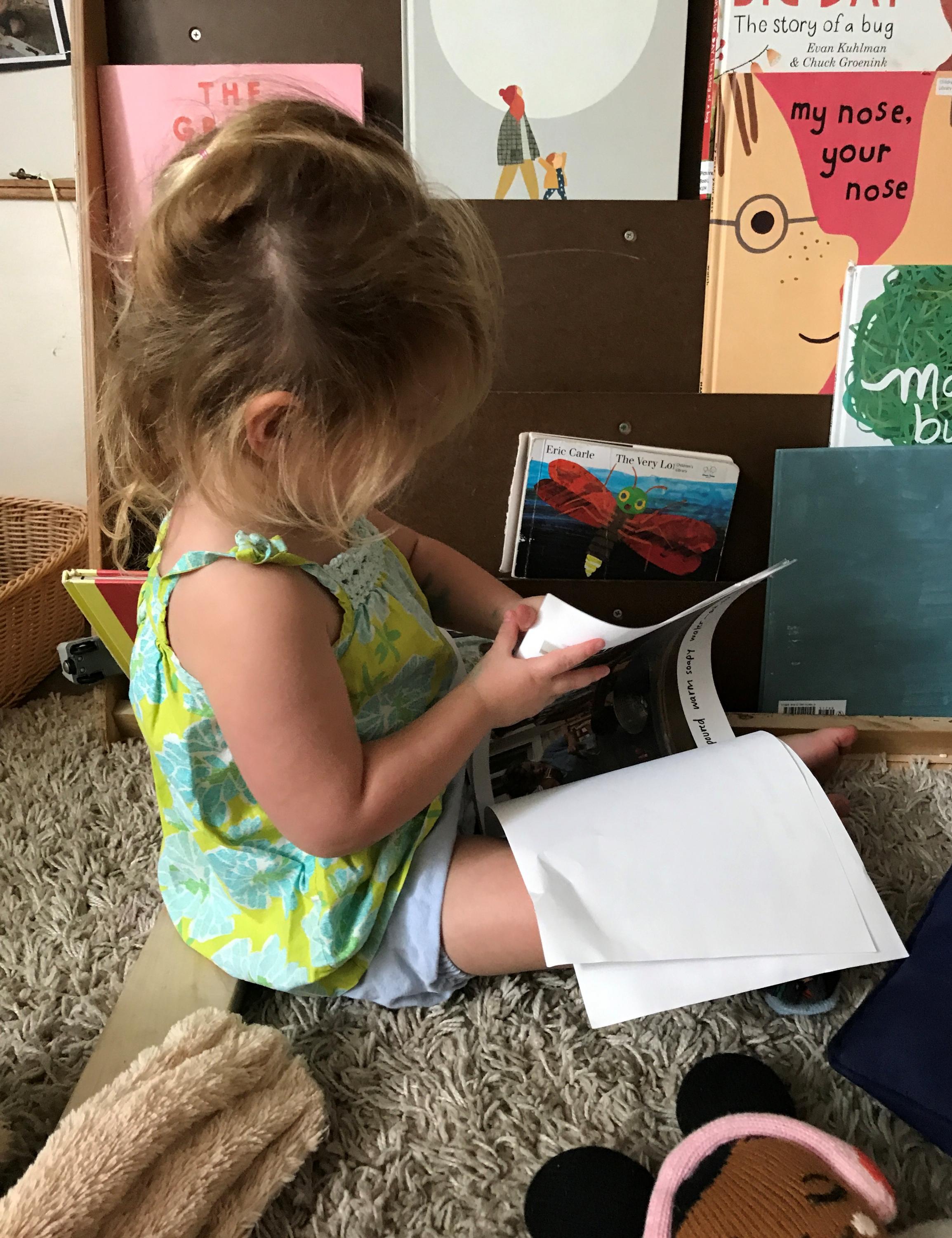

Next, I printed the booklets, stapled them together, and put them out for children to access. Although they began in a basket, I eventually placed them on the bookshelf and let the children engage with them during choice time, open-ended play, and other parts of our day.

To collect information related to my research questions, I observed the children on the reading rug throughout the day to see how they responded to the stories. I recorded interactions and conversations on paper and by video, including discussions the children had with me. Other times, busy with classroom duties, I snapped a quick picture to return to later and added written notes about what had occurred. These qualitative observations comprised the dataset for this study.

With the information I gathered, I combed through my notes, videos, and photos, all with an eye toward displays of early literacy behaviors that occurred while the children engaged with the booklets. I transcribed videos, marked up photos with notes and connections, and, using Lee (2011) as a guide, noted instances of children’s emerging knowledge about books and reading and the social situations in which this knowledge was displayed. These included

With the information I gathered, I combed through my notes, videos, and photos, all with an eye toward displays of early literacy behaviors that occurred while the children engaged with the booklets. I transcribed videos, marked up photos with notes and connections, and, using Lee (2011) as a guide, noted instances of children’s emerging knowledge about books and reading and the social situations in which this knowledge was displayed. These included

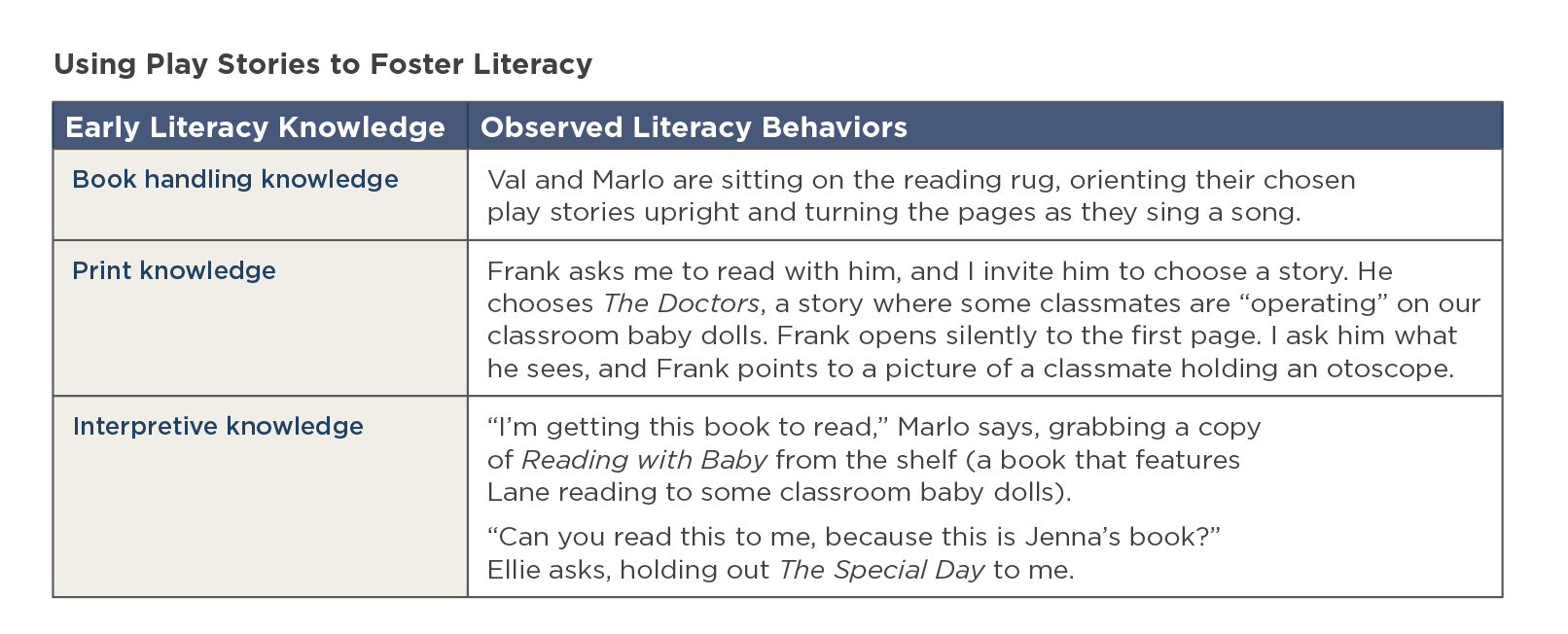

- book handling knowledge (holding a book in an upright position, turning pages, knowing where to begin reading on a page)

- print knowledge (pointing to pictures vs. print when asked to show where to read, understanding that print carries meaning)

- interpretive knowledge (showing enthusiasm for reading a book, describing pictures while going through a book, linking pictures or the content of a book to personal experiences)

Findings

Finding 1: Play Stories Are Legitimate Texts

The data revealed that the children treated play stories as legitimate texts. Children used the play stories as springboards to create stories and narratives—sometimes related to the original play stories, and sometimes taken in new directions—and they asked teachers and other adults to read the booklets to them. The children even referred to the play story booklets as “my friend’s book,” using the name of the peer most frequently featured in the text. In their schemas, these texts were not merely artifacts, but personal artifacts with personal and often immediate relevance.

From Field Notes, September 25

Rae chooses Spike, the story of a dinosaur figurine the children created stories for during play. Rae is featured on the first page. As she sits down to look at Spike, she points to herself.

“Oh!” I offer, demonstrating my own interest in the story.

Rae exclaims: “Me, me, me! Me! Me!

“It’s you, Rae!” I exclaim, laughing.

Rae continues to look at herself. In the picture she is holding some human figurines as well.

“Yeah,” she says, “getting the people.”

Here, Rae connects with the picture of herself before continuing on to engage with the story. She is overcome with excitement at seeing herself at play, and this provides an entryway to further interaction with the play story.

Finding 2: Play Stories Elicit Early Literacy Behaviors

The data also showed that children used the play story booklets to engage in the sorts of emergent literacy behaviors that early educators are striving to observe. These included orienting books correctly, attending intently to pictures (and possibly, over time, print), starting to narrate texts independently, and making connections between the texts and their own lives.

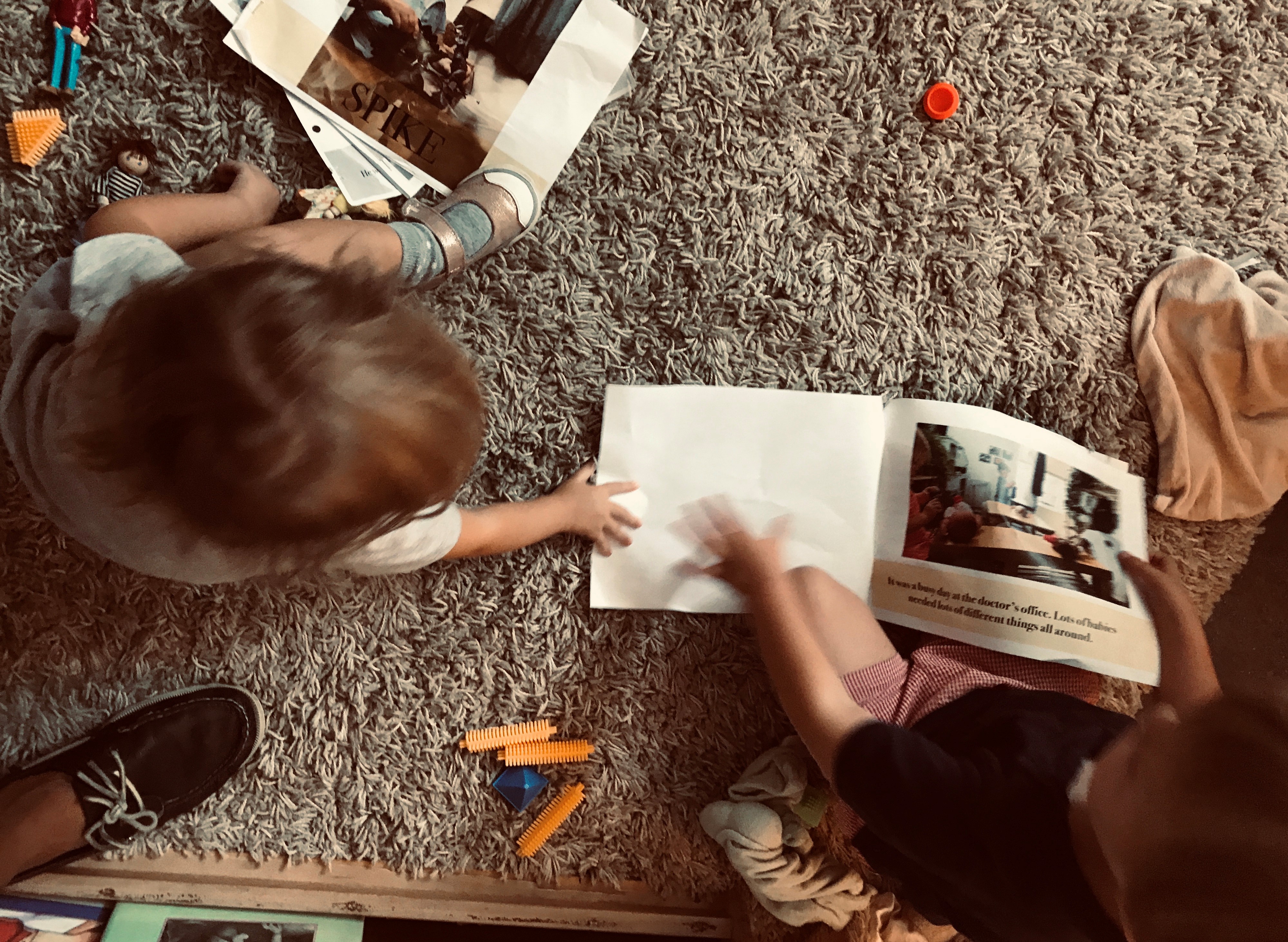

The table below further elaborates the data, featuring particular literacy behaviors detailed in Lee (2011) that were replicated in the current work. This underscores my findings about the use of play stories as legitimate tools for fostering literacy behaviors.

Each of these findings suggests that play stories are valid texts that children see as important and meaningful. More important, these stories may be a useful way to promote and observe early literacy behaviors in children as young as 2 1/2, as in this excerpt:

From Field Notes, October 23

My associate teacher, Meghna, and Ellie (2 years, 10 months) are sitting on our classroom reading rug in the morning, before other children arrive. Ellie chooses The Special Day, one of our play stories, to read. Over the course of this five-page book, Jenna is featured. She lays down on some pillows, plays with friends, explores with dinosaurs in a sensory bin, and talks to some friends from a window. On the cover, she is lying on a pile of pillows, with a smile across her face.

“Do you want to read The Special Day?” Meghna asks, sitting next to Ellie. Ellie nods, and Meghna leans in closely to listen.

“Now the girl . . .” Ellie begins, narrating while she looks at the picture that shows her friend Jenna lying on a pillow. Although I cannot hear Ellie clearly, the intention and inflection with which she tells the story is clear. She mimics our intonations—and then, satisfied with her reading, she flips the page.

Meghna, meanwhile, nods and audibly demonstrates her interest. Ellie flips to the page where Jenna is playing with dinosaurs in the sensory bin. Jenna is turned slightly toward the camera and is regarding the plastic figurines with a broad smile. Ellie continues to narrate: “The dinosaurs, she dipped it back into the water!”

Although Ellie was not reading words, she was connecting with and attempting to convey the meaning of text.

Finding 3: Play Stories Encourage Future Play

From Field Notes, September 17

I am on the reading rug, and Jenna approaches me. She looks at a play story featuring her classmates washing babies (The Dirty Babies, from August) and turns to me.

“Let’s do it again,” Jenna says, “when we were washing the babies again.”

I am surprised, and I even ask Jenna to repeat herself.

“We can do it soon again if you want,” I say. “Maybe later this week?” The only reason I don’t run to the sensory bin right then and there is because we are preparing to transition to our outdoor playtime.

“Yeah week . . . We can do it next time,” she concludes.

While Jenna did not flip through the story here, she did engage with it to help her plan for future play. A few days later, we revisited the washing of the babies as a class—inspired by the request Jenna made. This interaction demonstrates the potential of play stories to serve as tools for reflecting on past play and planning for future play.

Finding 4: Play Stories Reflect and Connect with Personal Experiences

Because cultural relevance and personal connection can motivate children to engage with books (Capellini 2005; Souto-Manning & Martell 2016), play stories are a promising medium. Given that they occur within the child’s classroom, the situations depicted in them are inherently personal. They also provide a mirror into the various contexts—ethnic and racial, social, interpersonal, physical, and emotional—of children’s lives. The fact that these stories can be produced and printed quickly, cheaply, and involve a process (taking photos of children) in which most teachers already engage add to their appeal.

Implications for Using Play Stories in Early Childhood Settings

In this work, I found that 2- and 3-year-olds treated the play story booklets in ways similar to traditional storybooks. They were eager to engage with them, they expressed pleasure in the pictures, and they made connections between the books and themselves. This investigation illustrates a potentially underused resource for early literacy—children’s play. It suggests that creating an environment that values and infuses both literacy and play is possible and that using play as the basis for literacy learning has many benefits.

In this work, I found that 2- and 3-year-olds treated the play story booklets in ways similar to traditional storybooks. They were eager to engage with them, they expressed pleasure in the pictures, and they made connections between the books and themselves. This investigation illustrates a potentially underused resource for early literacy—children’s play. It suggests that creating an environment that values and infuses both literacy and play is possible and that using play as the basis for literacy learning has many benefits.

Such findings, I hope, will inspire early childhood educators to incorporate extended periods of open-ended play in their settings. I hope that with that intentionality, they can advocate and share clear rationales for the integration of child-led play and early literacy. Based on what I learned, here are suggestions for meaningful connections between play and early literacy in early childhood settings:

- Keep play stories in a prominent place in the classroom and treat them with the same respect as you do other texts.

- Compare and contrast children’s play stories to other related texts and use play stories as inspirations for selecting new and different texts to bring into your classroom.

- Use play stories—and children’s interactions with them—to document emergent competencies in traditionally academic and social and emotional domains.

- Share play stories with children, families, and colleagues!

Although we did not have an opportunity to use these stories during read alouds, this would be an exciting extension of the work. Using play stories as whole-class read alouds would likely deepen children’s appreciation for their own and others’ play. It would reinforce the text-to-self connections upon which this work relies. Read alouds also could provide opportunities for children to discuss the conflict-resolution and emotion-regulation strategies necessary for continuing the play documented in the stories.

Play stories and the methods used to create them are accessible to anyone. Families and other caregivers may want to create booklets to engage children in early literacy experiences outside of early education settings, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and concurrent changes to the landscape of early childhood education. These narratives can authentically reflect these families’ linguistic and cultural practices.

One last enhancement would be to incorporate children’s own words more thoroughly into play stories, melding this work with methods pioneered by Vivian Paley (Paley 1981). This approach would invite children to give their own words entirely to the series of photographs. For children who are more comfortable and experienced with storytelling language, along with those who are less so, this is an opportunity to apply a valuable emergent skillset to an immediately relevant, personal experience.

Voices of Practitioners: Teacher Research in Early Childhood Education is NAEYC’s online journal devoted to teacher research. Visit naeyc.org/resources/pubs/vop to

- Peruse an archive of Voices articles

- Read the Fall 2020 Voices compilation

References

Bodrova, E. & D. Leong. 2015. “Vygotskian and Post-Vygotskian Views on Children’s Play.” American Journal of Play 7 (3): 371-388.

Capellini, M. 2005. Balancing Reading and Language Learning. Portland, Maine: Stenhouse.

Clark, A. 2017. Listening to Young Children, Expanded Third Edition: A Guide to Understanding and Using the Mosaic Approach. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Clay, M. 1975. What Did I Write? Beginning Writing Behaviour. Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Heinemann.

Corsaro, W.A. 2012. “Interpretive Reproduction in Children’s Play.” American Journal of Play 4 (4): 488-504.

Diamond, A., W.S. Barnett, J. Thomas, & S. Munro. 2007. “Preschool Program Improves Cognitive Control.” Science 318 (5855): 1,387–1,338.

Dickinson, D.K., & K.E. Sprague. 2001. “The Nature and Impact of Early Childhood Care Environments on the Language and Early Literacy Development of Children from Low-Income Families.” In Handbook of Early Literacy Research, eds. S.B. Neuman & D.K. Dickinson, 263-280. New York: Guilford Press.

Einarsdottir, J. 2005. “Playschool in Pictures: Children’s Photographs as a Research Method.” Early Child Development and Care 175 (6): 523-541.

Hendrick, J. 1997. First Steps Toward Teaching in the Reggio Way. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Merrill.

Hirsh-Pasek, K., R. Golinkoff, L. Berk. & J. Singer. 2009. A Mandate for Playful Learning in Preschool: Presenting the Evidence. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kuschner, D. 2012. “Play Is Natural to Childhood but School Is Not: The Problem of Integrating Play into the Curriculum.” International Journal of Play 1 (3): 242-249.

Lee, B.Y. 2011. “Assessing Book Knowledge Through Independent Reading in the Earliest Years: Practical Strategies and Implications for Teachers.” Early Childhood Education Journal 39 (205): 285-290.

Mardell, B., J. Wilson, J. Ryan, K. Ertel, M. Krechesvsky, & M. Baker. 2016. Towards a Pedagogy of Play (Project Zero Working Paper). Retrieved from: http://www.pz.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Towards%20a%20Pedagogy%20of%20Play.pdf.

McNamee, G. 2015. The High Performing Preschool: Story Acting in Head Start Classrooms. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Paley, V. 1981. Wally’s Stories: Conversations in Kindergarten. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Paley, V. 2004. A Child’s Work: The Importance of Fantasy Play. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Roskos, K., & J. Christie. 2011. “The Play-Literacy Nexus and the Importance of Evidence-Based Techniques in the Classroom.” American Journal of Play 4 (2): 204-224.

Roskos, K.A., J.F. Christie, S. Widman, & A. Holding. 2010. “Three Decades in: Priming for Meta-Analysis in Play-Literacy Research.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 10 (1): 55-96.

Saracho, O.N. & B. Spodek. 2006. “Young Children's Literacy‐Related Play.” Early Child Development and Care 176 (7): 707-721

Serriere, S.C. 2010. “Carpet-Time Democracy: Digital Photography and Social Consciousness in the Early Childhood Classroom.” The Social Studies 101 (2): 60-68, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00377990903285481.

Souto-Manning, M. & J. Martell. 2016. Reading, Writing, and Talk: Inclusive Teaching Strategies for Diverse Learners, K–2. New York: Teachers College Press.

Stacey, S. 2015. Pedagogical Documentation in Early Childhood. St. Paul, Minnesota: Redleaf Press.

Sulzby, E. 1985. “Children's Emergent Reading of Favorite Storybooks: A Developmental Study.” Reading Research Quarterly 20 (4): 458-481.

Wurm, J. 2005. Working in the Reggio Way. St Paul, Minnesota: Redleaf Press.

Photographs: Courtesy of the author

Copyright © 2021 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

Ron Grady is a PhD student at the Harvard Graduate School of Education in Cambridge, Massachusetts.